1. 16th CENTURY

a) El Escorial Building History

The planning of the Escorial monastery began in 1561, one year before its final site was marked out.

Fray JOSÉ DE SIGÜENZA stated that this was a rectangular area (226×177 m) with a subsidiary area to the east (40×55 m) intended for the royal apartments, under the traditional Spanish custom of joining residences for the monarch to the principal royal monasteries.

The ground plan, the ‘universal’ design made by Juan Bautista de Toledo, has been regarded as representing the grid on which St Lawrence was martyred. It is surrounded by a portico at the northwest, the royal gardens to the east, and the monastery gardens to the south. This layout was retained throughout the numerous subsequent modifications.

The entire western area, planned as the monastery house and college, was to have been at a lower level than the rest of the building and separated from the eastern region by two towers; the latter was removed from the plan in 1564, leaving only those at the four corners of the complex.

Similarly, the church, based on Michelangelo’s design for St Peter’s, Rome, was to have had two eastern towers flanking the sanctuary and over the rooms of the king and queen and two others on the west façade of the complex.

These towers, with cupolas characteristic of formal palace architecture, can be seen in the designs attributed to Juan Bautista, which show alternative plans, one with a double order, the other with a giant order.

Other designs show the future Patio de los Reyes (between the leading portal and the church) with an open gallery.

In January 1563, before building began, the members of the advisory Council of Architects, Pedro Fernández de Cabrera y Bobadilla, 2nd Conde de Chinchón, Martín Cortés, 2nd Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca, and Pedro de Hoyo, the Secretary, decided to use the overall design of Juan Bautista with the church design of Paciotto and some details of a plan by Gaspar de Vega.

Further changes were made in 1564 when it was decided to double the number of monks from 50 to 100.

Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón and Hernán González de Lara visited the construction and, from the viewpoint of architects trained in Gothic building techniques, criticized details of the overall plan and the church plan by Juan Bautista. Finally, on the advice of the Obrero Mayor, Fray Antonio de Villacastín, the whole complex was brought to the same level as the east side. This required changes to several elevations and modifications to the church design, which were incorporated into a section drawing by Juan Bautista.

By the death of Juan Bautista in 1567, the foundations of the whole of the south section had been laid. Work had begun on the south and west façades, the Patios Chicos, the Old Church, the Pantheon crypt, the Patio de los evangelistas, and the private royal apartments, including the Patio de los Mascarones and perhaps also the Galería de los Convalecientes, which is next to the south-west tower and undoubtedly of Serlian character. All of these reflect the style of Juan Bautista. There was an interval in the planning process until Juan de Herrera took complete charge of the building in around 1570.

Meanwhile, Giovanni Battista Castello had begun work on the main staircase (1568) to his design, but this was demolished in 1571 to make way for the open-well imperial stairway designed by Herrera. Various plans for the church had been sent to Florence for submission to the Accademia del Disegno in May 1567, and further contacts were maintained with Italian architects.

In 1571, Pellegrino Tibaldi sent a design for the church, and Philip II commissioned Barone Gian Tommaso Marturano to collect further plans, including designs by Galeazzo Alessi, Andrea Palladio, and an oval design by Vincenzo Danti. These were submitted, probably with others by Spanish architects, for consideration by the Accademia in Florence and were then reworked by Jacopo Vignola in Rome into a new design that was presented to Pope Gregory XIII in 1572 and sent to Spain in 1573.

Work nonetheless continued, and the foundations of the basilica were laid. Two models were constructed in 1570 by Diego de Alcántara and Martín de Aciaga. The church’s first stone was laid in 1574; it was completed in 1584 and consecrated on August 30, 1586. From 1571, the Hieronymite Order occupied the conventual buildings, and during 1573 and 1574, the remains of several royal persons were temporarily translated to the Old Church.

In 1573, work on the north façade began, and in 1581, work also started on the courtyards of the Colegio and seminary. A contract was drawn up for the principal west façade in 1574. The Doric tempietto in the Patio de los Evangelistas was built between 1586 and 1591, also to designs by Herrera.

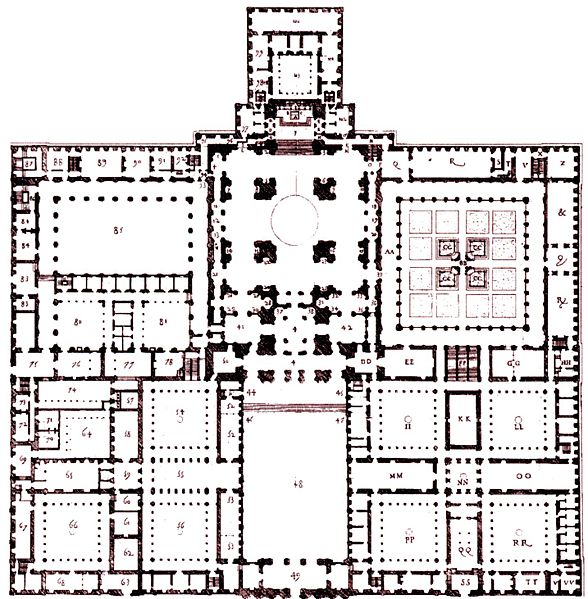

b) El Escorial Plan

From a functional point of view, the El Escorial can be divided into three main sections from north to south, each with an independent entrance from the west front.

The central section of the western elevation, which the library occupies, is higher than the rest of the façade in the manner of Spanish university libraries. Its façade is of a pastoral type derived from Serlio, with two orders of superimposed columns and a pediment.

Beyond the bare, austere, rectangular Patio de los Reyes are the basilica and the private royal apartments built around the Patio de los Mascarones. Two towers flank the church, and its façade has two main storeys, a triple arched portico, Doric half columns for the lower level, and pilaster-strips supporting a pediment for the upper one.

With its centralized planning and Roman character, the church broke decisively with Spanish ecclesiastical design traditions. Through the narthex is a public chapel, a centralized area situated beneath the monks’ choir and covered by a remarkable flat sail vault, with a floor plan that repeats the main and private body of the basilica but on a much smaller scale. The church is organized as a Greek cross within a square, and this central area was inspired by Michelangelo’s St Peter’s Basilica, but with the original apses squared like Alessi’s S Maria Assunta in Carignano, Genoa. The cupola of the latter had a direct influence on that of the Escorial, which was the first in Spain to be built with a drum. The principal arms of the cross have barrel vaults; the corner areas have sail vaults and a high gallery runs around the inner perimeter.

The interior is articulated with fluted Doric pilasters without pedestals. As a result, there are inconsistencies at the juncture of the raised presbytery, which is flanked by the imperial and royal sepulchers. This leads east to the oblong Sagrario, open towards the principal retable and giving access to the monstrances. The church is connected to the austerely decorated private royal apartments on the south side, and an opening to the presbytery allowed the king to contemplate the high altar from his bedroom. The focal point of the palace is the two-story Patio de los Mascarones, with arches supported by columns on one level and galleries on three sides. It is reached through a long room on the east side and gives access to the queen’s chamber on the north side.

The monastery occupies the south sector and has a simple entrance in the western elevation, with a projecting attic crowned by a pediment. The west part of this zone has a cross-shaped layout with four courts (the Patios Chicos) of a simple Tuscan design. The first two belong to the hospice and infirmary, while the eastern pair forms part of the monastery. At the center is a tall vestibule, topped by a tower and spire, leading to four rectangular halls housing the kitchens to the west and the refectory to the south. The eastern half of this zone is occupied by the great Patio de los Evangelistas (nearly 50×50 m), enclosed by two storeys of arches upon piers with Doric and Ionic half columns, in a composition derived from the courtyards of the Palazzo Venezia and the Palazzo Farnese, both in Rome. At the center is the small, octagonal tempietto, with a granite exterior and marble and jasper interior, topped by a cupola and surrounded by four square pools.

The seminary and Colegio of the northern sector are also entered from the west front and organized in the shape of a cross. The western arm of the cross contains the restrooms; the southern arm, with its open gallery, became an ambulatory; the eastern cape houses the refectory; and the northern arm the kitchen. Lecture halls were arranged along the west front with lodgings above. The east range was set aside for the royal palace. It had two entrances through the north façade and a large central courtyard, similar to the Patio de los Evangelistas, although with pilasters rather than half columns. It was separated in its western part into two small yards to provide access on both levels to the lodgings of noblemen and royal persons. The north wing included the palace staircase and rooms for ambassadors. In contrast, the upper floor of the south wing became a private walk or royal gallery, providing entrance to the private apartments of the palace and the church.

In the 1580s, building work began on various annexes and service areas. Herrera designed the first two Casas de los Oficios to the northwest, bordering the lonja, and the Casa de los Doctores farther to the north. Francisco de Mora designed the pharmacy, the stairway, and the orchard pond at the southwest corner of the monastery, next to the Galería de los Convalecientes. During the 1590s, he built the Casa de la Compaña to the west and the smaller Cachicanía (gardener’s cottage) and Pozo de Nieve (ice-house) south.

2. Later Developments

The most important addition to the monastery in the 17th century under Philip III was the Panteón de los Reyes, designed by Giovanni Battista Crescenzi between 1617 and 1618. Juan Gómez de Mora, Fray Nicolás de Madrid, and Alonso de Carbonel supervised its construction.

The octagonal underground chamber, decorated with pilasters, inlaid marble and jasper, and bronze-gilt capitals, represents the reintroduction of an ornamented style in Spanish architecture and is one of the sources of Spanish Baroque decoration.

The Escorial expanded under Juan de Villanueva, who built the third service building, the Casa de Oficios, the Casa de Infantes, the Casitas de Arriba y Abajo, and the residences of the French consul and the Marqués de Campo Villar during the 1770s and 1780s.

Alterations were made to the north front and the interior of the royal palace of the Bourbons, with its new staircase. During the reign of Isabella II, work began on the Panteón de Infantes under the architect José Segundo de Lema.

3. Sources, symbolism and influence

From the 1570s until the mid-17th century, and even beyond, the Escorial enormously influenced Spanish architecture. It epitomizes the classicism of the age of Philip II and the figurative arts practiced then by Spanish and foreign artists. It is also a testimony to the continuous evolution of Spanish art up to the 19th century. Its influence on planning major architectural projects elsewhere in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries was widespread.

The Escorial’s sober and monumental architectural style, with its treatment of the Classical orders, has been placed within the framework of international Mannerism and in the movement from the Renaissance to the Baroque. It is, however, generally accepted as an example of the classical style advocated by Philip II, who controlled all the planning and construction processes, based on an orthodox handling of the models established in ancient Rome and contemporary Italy and submitted, principally by Herrera, to a method of geometric abstraction and formal simplification.

There has been extensive discussion concerning the ultimate responsibility for the edifice, with critics attributing the onus of the design variously to Juan Bautista de Toledo or Juan de Herrera. Despite some subtle qualifications, the 16th-century construction is characterized by its coherence and would seem to be the work of one team led by the King. The building history suggests that Juan Bautista established the outlines of the design and that Herrera, whom Juan Bautista trained, accepted the legacy and only introduced modifications.

The ideology behind the design has also been the subject of debate. Traditionally, it has been considered the embodiment of the most orthodox spirit of the Counter-Reformation and a reflection of the rigid mentality of Philip and Herrera. The possible influence of hermetic thought and the mysticism of the philosopher Ramón Lull has been suggested, with the Escorial being conceived as a new Temple of Jerusalem, despite Sigüenza’s rejection of formal links between the monastery’s design and the Temple of Solomon. It has also been seen as relying on Early Christian principles, especially on such early models as the aesthetics of St Augustine, as embodied in his City of God. Another suggestion, drawing on the writings of both Sigüenza and Herrera, is that it revived a Christian tradition of classical architecture, evident in its use of orders, its system of proportions, and its ‘cubism’ or block-like design.